Shaolin Storytelling and Wu-Tang Writing

Having Hi-Yah Hopes for a B-movie Genre

I’m going to be honest, this post is partially inspired by an Instagram reel of a clip from The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter. However, this post was a long time coming: my father enjoyed watching kung fu movies while he was alive, and I would occasionally sneak a watch with him. I still have vague memories of the opening scene from Kung Fu Hustle (2004), a movie that I would revisit years later when my mother could no longer shield my eyes from what is otherwise a pretty well choreographed but very slapstick movie.

Kung Fu Hustle is, in my opinion, one of the few kung fu movies that has a message that reaches beyond “train hard, fight hard, win hard”. Which, admittedly, can be somewhat reductive of the genre as a whole. Of course, there are movies worth talking about that do have messages, or at least strong themes; then again, the reason they are worth talking about is because they are actually movies of substance and quality.

For example, the film Fists of Fury, starring the singular Bruce Lee, deals headfirst with the issue of Japanese colonialism and Chinese patriotism, identity, and self-sufficiency. The message of this film is, I think, essentially a self-affirmation of China’s identity, history, and strength as a nation in the face of foreign imperialism and oppression. And while more modern films like Ip Man (2008) starring Donnie Yen do continue this theme and discussion, I do feel that this overall theme of Chinese self-sufficiency (the superiority complex and propaganda do crop up over time as well) has since been watered down from the days of Bruce Lee. Even Ip Man, though a pretty decent martial arts movie, often feels more like spectacle than substance, but I digress.

The kung fu genre as a whole is, to be frank, a B-movie genre. There are, of course, gems and studios worth talking about (I’ll get into that in a second), but for the most part kung fu movies have always been relatively low budget, with most of it going towards the fight choreography. For example, look at these costumes from Clan of the White Lotus (1980):

Even in these low-quality screenshots, the costumes look so cheap, it looks like they just printed some designs out on paper and taped it to his chest.

But I don’t mean to dog on kung fu movies too hard: at least up until the 90s, budget was always a limitation of the genre, even with bigger productions and bigger studios. However, it would be a little bit myopic to ignore the fact that, for most kung fu movies, spectacle came first, and storytelling second. But that is not to say it’s impossible, and there are some fantastic examples that exist with what I feel are interesting themes, or at least more complicated messages than “fight good, hit hard, win big”.

The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter (1984)

The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter was made by the film production company Shaw Brothers, which was actually at one point the largest Hong Kong film production company. So, at least for Shaw Brothers films, they could afford to have nicer sets, bigger budgets, better effects and props, and, most famously, the greatest fight choreography. And this film was directed by the legendary Lau Kar-leung, who also did the stunt choreography for Jackie Chan’s Drunken Master II.

Clan of the White Lotus was also made by Shaw Brothers, which does make them look bad; but as a whole, Shaw Brothers films do tend to look better than most other kung fu movies of their time. I do still think that the production holds up for what it is, and it is always done in service of the fights, which are the most important part of kung fu movies.

Ok, time for the part that actually matters.

The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter is, in my opinion, the best Shaw Brothers film, thanks to its choreography, its passionate (if still stiff) acting, and just how genuinely heartfelt it is. This film stars Gordon Liu, known in the West for playing Pai Mei in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill.12 Also in this film are Kara Hui, a famous stuntwoman, and Alexander Fu Sheng, who sadly died during production.

The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter, like many kung fu films, is really just a drawn-out revenge story with training added in. Except I think in this film it lands really well. The film is based on the Chinese folklore collection The Generals of the Yang Family, documenting the history of a respected military family.

The film opens with the Yang3 patriarch and his seven sons, all of them trained in the military arts of the spear, doing battle against the Khitan-ruled Liao dynasty.

To make a long story short, it does not go well: the Yangs are betrayed by the Chinese general Pan Mei, like lambs to the slaughter. To rub salt in the wound, the Liaos have developed a whip-style staff to nullify the Yangs’ spear technique. All but two of them die, Fifth Yang (Liu) and Sixth Yang (Sheng). Initially, Sheng was meant to be the star, but was replaced due to his death; his scenes remain in the movie, and they actually do carry significant weight, but much of his arc is folded into Liu’s character, namely the PTSD aspects.

But anyways, after this betrayal, Fifth Yang retreats to a Buddhist monastery, guilt-ridden and unable to return home lest he put his mother and two sisters, Eighth Sister (woe! Hui’s character only gets to be called “sister” and not Yang) and Ninth Sister.

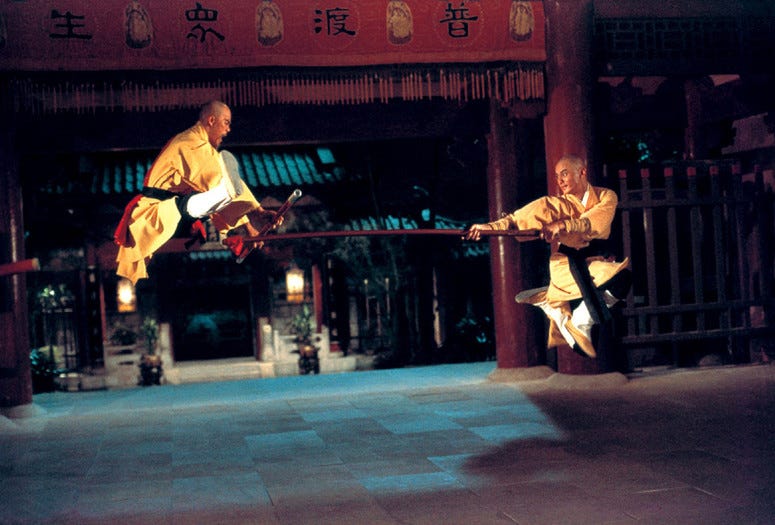

This is where the movie really starts to get interesting for me. Look at how he enters the Buddhist monastery:

He is wearing a disguise, not his armour and battle regalia. He is unshaven, his eyes watery, he is a shadow of his former self. Even his beloved spear has changed, for the new whip-style staff that the Liaos forced him to cut off the spear, which is also done to help disguise him.

All in all, he physically shows that he has been changed by war, and certainly not for the better.

At this point in the film, it is clear that he is essentially joining the monastery somewhat for the wrong reasons: he bears an immense anger and sorrow, partially directed at himself, but mostly at Pan Mei and those who wronged him and his kin. In other words, he is displaying signs of PTSD. In his almost trancelike state, he even applies the jieba, the dots on Buddhist monks’ heads, unevenly and callously, instead burning himself severely. The abbot even says as much, that he isn’t fit to be a monk.

As he continues to spend time at the monastery, he shows that he is unable to adapt to their pacifistic beliefs, even challenging one of the abbots during a training session. Here, the abbot is demonstrating how they deal with the threat of local wolves, choosing to only defang and apply enough strikes to scare them off:

In this scene, Fifth Yang directly challenges the abbot and Buddhist beliefs of pacifism, where Fifth Yang belligerently argues that to drive off the wolves, they must be viciously dealt with and made an example of.

But it is a later scene where the main question of the movie is explicitly asked.

See, Eighth Sister, a skilled martial artist in her own right, went on her own journey to find her missing brother after hearing about him from one of the monastery abbots. Sadly, this abbot was murdered by the Liaos, thus making finding him more difficult. Word reaches Fifth Yang that his sister has been captured by the Liaos, which delivers this amazing fight scene:

Fifth Yang: My sister is a woman, but she’s brave.

Abbot: The worldly matters have nothing to do with me.

Fifth Yang: The Buddha has a weapon to fight the evils, so it’s only normal that I do what’s right.

There it is: if I have the means to fight injustice and evil, shouldn’t I be able to at least try and stop it?

What follows, of course, is one of the best fight scenes in any kung fu movie. Liu’s character summarily beats the abbot, demonstrating the eponymous “Eight Diagrams” technique.4

And I think this is genuinely an underappreciated aspect of the movie, where it reaches beyond basic themes and ideas of familial loyalty and brotherhood and vengeance. This film genuinely asks under what circumstances is it justified to enact violence, and whether one is morally culpable for having the means to correct injustices and evils but choosing not to do so.

The film answers its own question during the big choreographed fight at the end, when Fifth Yang runs off to rescue Eighth Sister:

As evidenced by this image, the abbot has joined Fifth and Eighth Yang in their fight against the Liaos, along with a squadron of monks. Here, the abbot has fully come to agree with Fifth Yang (he shouts “Kill!” in the original Cantonese and English dubs), coming to agree that evil must be stopped, and it must be done swiftly and painfully.

Now, to be honest, the pacing of this movie, like most kung fu movies, is kind of all over the place, which makes sense given the production history. And part of me wants to nail this film for having what is a bit of a simplistic answer to the question of how to deal with injustice. But I think that’s just nitpicky, and one should really appreciate this film for asking and presenting something complicated.

Remember, Fifth Yang is not a typical action hero, and not even a typical kung fu movie hero: at the start of the movie, he is already incredibly skilled at martial arts, but his world is torn down right in front of him. Yes, he trains, and like any kung fu movie it is shown. But it is the very fact that he is not a cool, level-headed fighter of few words, or a stoic patriotic fighter, or even a goofy slapstick fighter with a heart of gold. No, he is a traumatised soldier who grapples with serious questions when he wants to change and leave behind his past, but is unable to do so.

And I think that’s what makes this movie the best Shaw Brothers movie.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon probably needs no introduction, but I might as well give one for those not in the know.

Directed by Ang Lee, of Brokeback Mountain, Hulk, and Eat Drink Man Woman fame, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is a film with numerous interpretations, so I’ll just pick one that I think is worth talking about, one done with brilliant visuals from Lee and Yuen Woo-ping, also known for his choreography work on Kill Bill and The Matrix.

The message is tied to the main plot device of the film, the sword Green Destiny, an invincible, impossibly sharp sword carried by the well-known swordsman Li Mu Bai. In the backstory of the film, Mu Bai long harboured feelings for Yu Shu Lien, who reciprocated, but was engaged to their mutual friend. Basically, they yearn for each other but feel that they can’t be honest about it out of loyalty to their dead friend.

The sword Green Destiny is eventually stolen by Yu Jiaolong, or Jen, the daughter of the local governor and soon to be one half of an arranged marriage. Jen also has her own forbidden love, but one that she has been able to act upon: as is shown, prior to the start of the movie, Jen was kidnapped by but fell in love with the roguish Lo, who once attacked her travelling caravan.

Jen absconds with Green Destiny, waving and swinging her skills (bad pun intended) at any who even look at her wrong:

However, later, as she fights Shu Lien, Shu Lien quickly proves that while Jen is undeniably talented, she can still lose. Though Green Destiny can cut through any weapon put to its edge, it ultimately cannot overcome the gap in experience between Jen and Shu Lien. More importantly, she is overly reliant on the sword as a marker of her skill and identity as a fighter and as a person. It is something Mu Bai echoed earlier in the film:

Like most things, I am nothing. It's the same for this sword. All of it is simply a state of mind.

And it is something Shu Lien independently agrees with, though she is much more accusatory and antagonistic:

Without the Green Destiny, you are nothing.

At the end of the movie, Jen gives up Green Destiny and travels to meet Lo at Mount Wudang, the school from which Mu Bai hails. Once there, Jen asks Lo to make a wish, to which he responds:

To be back in the desert, together again.

From there, Jen floats off the mountain, and their paths remain open; unsure, yes, but their paths are their own.

Part of the movie’s message should be obvious: to live earnestly and in tune with one’s truest inner feelings and desires. But I think it does go deeper than that. I think that one of the questions that the movie is really trying to get the reader to ask is that without special skills, or weapons, or even reputation, who am I? What do I want and care about?

And I think Green Destiny ties a little more into that message than people tend to give it credit. The name Green Destiny is clearly a little bit on the nose: several characters literally wield destiny in their hands. But Green Destiny is certainly meant to represent more than that.

First is that tying one’s identity too closely to something or someone external essentially robs oneself of any genuine growth, skill, or just plain identity. Mu Bai, for example, is famed for his skill in spite of, not because of Green Destiny. In contrast, Jen relies too much on the reputation and the actual qualities of Green Destiny to bolster her own identity of self, using the sword to make her feel more independent and self-assured than she actually is or deserves to be. This is one that she learns by the end of the film as she gives up the sword; though she has not fully developed herself yet as a fighter and as a person, she is certainly on the way there.

Second, and somewhat relatedly, Mu Bai and Jen both learn how to actually be in control of their own fates and feelings, with regards to themselves and others, but only after both have given up Green Destiny. Thus, there is some irony in the fact that wielding Green Destiny both helped to guide them towards their fully developed identities and selves, but it is only after giving up the legendary sword that they are truly able to choose an authentic fate for themselves. With his dying breath, Mu Bai is able to affirm and confess his love for Shu Lien; Jen, for her part, does not exactly know where she will go next, but she takes a leap of faith, newly equipped with the wisdom to face whatever she chooses.

I really do believe that one of Ang Lee’s goals with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was to inspire the viewer to look deep within themselves and ask the above question by stripping away as many of our own externalities as possible. The inclusion of Green Destiny was important because it exists, I think, to make itself redundant. It’s not supposed to matter despite its reputation or actual qualities as a sword. Green Destiny is there to represent the meaningless weight of societal pressure, while simultaneously represent how talent or ambition without the wisdom to guide it is equally meaningless.

Kung Fu Panda (2008)

It may be the case that Kung Fu Panda needs no introduction, at least for a Western audience, but I think it might be useful to have a refresher, just in case.

In Kung Fu Panda, Jack Black’s character Po is a fat panda with no skill in martial arts working a dead end job at his father’s noodle shop.

He does have one thing going for him, though: a deep appreciation for, and one may even say an obsession with the Furious Five, a group of five martial artists that are conveniently animals that exactly match the styles of kung fu which they practice.

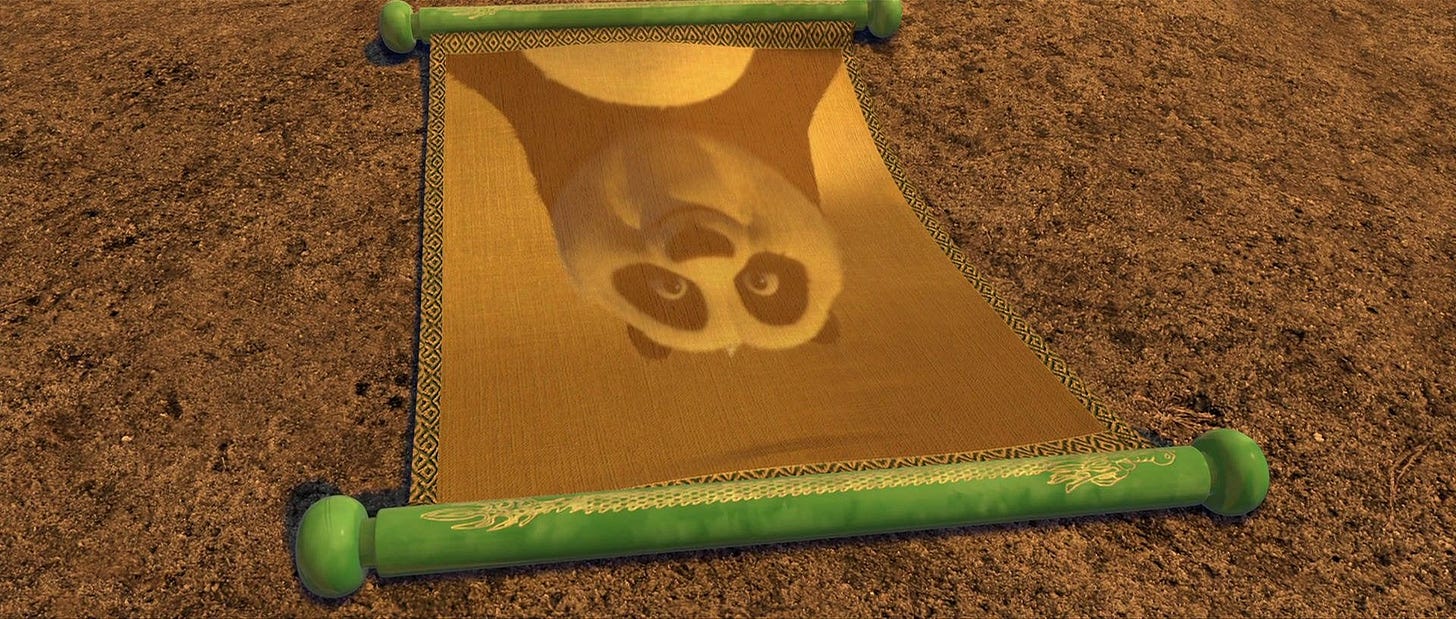

Po is, in other words, a fat American kung fu nerd. Except he’s more than a fat American! He’s also the Dragon Warrior, prophesied to become the greatest master of kung fu that there is.

Through a few mishaps, Po eventually becomes the Dragon Warrior and defeats Tai Lung, a vicious and disillusioned student that used his kung fu for evil.

Being a kids’ movie, the primary message of Kung Fu Panda is quite literally spelled out for the viewer, and does not need some snot-nosed college kid at his desk to tell you what it is.

There is no secret ingredient…

Brilliant. Profound. Revolutionary, even.

There is, of course, the reverse to that message, which is that a meaningful relationship can take many forms, and that not all relationships are strictly transactional or conditional. Po, for example, is the adopted son of a goose; and while he is a smothering father, Mr. Ping undoubtedly loves his panda son. Shifu, likewise, loved Tai Lung like a son:

I have always been proud of you. From the first moment, I've been proud of you. And it was my pride that blinded me. I loved you too much to see what you were becoming. What I was turning you into. I'm... sorry.

There is a vaguely Confucian undertone to this that I think was unintentional from the writers. This theme of parenthood carries over into Kung Fu Panda 3, and I’d broadly argue that the overarching theme is that parents should always be honest with themselves about what their child needs, but I digress.

Anyways, Kung Fu Panda isn’t really reinventing the wheel here when it comes to messaging. And by virtue of being a kids’ movie, it has to be obvious and even a little simple with its message, but that doesn’t make it any less impactful or meaningful.

Rather, I kind of want to go out on a limb here and say that there’s something else in Kung Fu Panda that keeps it in dialogue with its kicking and punching predecessors, even to a meta level. And that message is, I think, all about doing things out of passion and reverence, which is something that the movie itself does explore, but the message genuinely goes beyond just the confines of the film.

In the film, Po’s passion and fanboyism, bordering on genuine obsession, is what catapults him into training kung fu: it’s what pushes him to go through training that, at least at first, constituted more abuse than teaching. The same went for its animators: per this New Lines Magazine article, the animators immersed themselves in the kung fu culture, through training it themselves, to watching and referencing classics like Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and The 36th Chamber of Shaolin. And, if you look at the Wikipedia for the film’s production, it is evident that a lot of care, but more importantly, genuine passion and love for Chinese culture went into the film, even if it wasn’t entirely accurate.

It was so passionate, in fact, that it caused a stir in China on how this American movie, produced in Hollywood, a beacon of Americana, made a movie like this before China did. Here’s a quote from the Washington Post in 2008 about the film:

Directors don't cherish the culture, and audiences want to watch Western things, so people don't think there's a big market for films about Chinese culture. Our education system only focuses on students' ideology instead of encouraging them to be creative. If we only watch ourselves from our position, we can't get the whole picture.

And another:

Why shouldn't we allow foreigners to make these kinds of movies? Sooner or later, Chinese people will realize that the best things we have are the things we already have.

And another:

"If people are educated only to pass exams, then it's very hard to be imaginative. Nowadays, this is an era when people are only stymied by a lack of imagination, not a lack of ability."

Last one, I swear:

The film's protagonist is China's national treasure and all the elements are Chinese, but why didn't we make such a film?

And this is something that one of my favourite channels on YouTube, Accented Cinema, also goes into:

In this video, Yang Zhang, the creator of the channel, ultimately summarizes thus:

This film loves China more than China loves itself.

To be clear, the purpose of including Kung Fu Panda is not to entirely rehash his video. I include Kung Fu Panda because I think the context surrounding this movie sends a genuine message about the nature of making a film that is steeped in culture. Especially in an era where representation matters and we care about how a culture is presented and appreciated, I think this kids’ movie just does an amazing job at showing that cultural accuracy isn’t everything. Kung Fu Panda sends an important meta-message about how genuine love and passion for a culture will always, always bear more fruit than just surface-level or performative representation. And that love was so apparent that it gave China an existential crisis.

Some sort of concluding header

Kung fu movies are a simple genre: fight, lose, get better, fight harder and better, win.

But, like any genre, there are always amazing gems that transcend the genre itself and can take on genuinely interesting conversations about morality, philosophies of life, and cultural appreciation and personal passion. And I think, to some degree, that films like Shaolin Soccer and Kung Fu Hustle arguably do this best by taking the kung fu genre and making it comedically self-referential. Because those two films, like Kung Fu Panda, take a genuine passion and turn it into great films worth looking at.

But beyond that, I think these three films just show a B-movie genre at its best, through genuine attempts to discuss ethics and morality, focusing more on philosophy and storytelling than fighting, and just through unbridled love, passion, and attention to making something that shows that it cares.

And, in a world where media and art are becoming increasingly commercialised and treated as a product rather than a work of art, I think these approaches to creation are more important than ever.

No matter what one thinks about Tarantino as a director, and whether he deserves the praise he gets or the title of auteur, one cannot deny that Tarantino knows his films. Real recognises real.

Gordon Liu also stars in the seminal film The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, another fantastic movie that partially names Wu-Tang Clan’s seminal debut album. Wu-Tang Clan is full of kung fu movie dorks like myself, and the Shaw Brothers influence shows in everything, from the samples, to the lyrics, to even their names.

Or, if you speak Cantonese like me, Yeung. It’s not a big difference. For example, Jimmy O. Yang, who is also Cantonese, goes by Yang (evidently enough).

This movie absolutely influenced Kung Fu Hustle. If you know you know. If you don’t, just watch the character Donut the baker. Fun fact, one of the characters in the movie is played by an actual Shaolin monk.